What does the draft US Senate IoT security bill mean for IoT vendors and researchers?

We have been calling for regulation, legislation and also litigation in the IoT security space for some time. I’ve spoken at the UK Parliament and briefed several government departments about the threat to consumers and the nation as a whole from poorly secured IoT devices, as have other researchers in the USA

We have been calling for regulation, legislation and also litigation in the IoT security space for some time. I’ve spoken at the UK Parliament and briefed several government departments about the threat to consumers and the nation as a whole from poorly secured IoT devices, as have other researchers in the USA

The good news is that much progress is being made, though legislation can be painfully slow to debate and enact. Some progress has been made in the EU, but the draft US Senate bill “Internet of Things Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2017″ is a fantastic step in the right direction. Page 2, lines 7-12 even contain a definition of firmware!

https://www.scribd.com/document/355269230/Internet-of-Things-Cybersecurity-Improvement-Act-of-2017

What does it mean for IoT manufacturers?

US departments and agencies will not be able to purchase non-compliant IoT devices, though a waiver can be issued, particularly for disclosed vulnerabilities. That means that if you want to sell to US gov, which is a pretty large market, you need to follow some standards, which I’ve attempted to summarise briefly:

- The device cannot have hardware, software or firmware vulnerabilities that are listed in the NIST vulnerability database or similar

- Must be able to receive authenticated and trusted software updates from the manufacturer

- Cannot use deprecated network and encryption protocols

- Must not have fixed or hard coded credentials for remote admin, updates or communication

- Newly found vulnerabilities must be disclosed to the customer

- Future update support – the clause in the draft bill does not state how long this must be for, instead referring to the customer contract, which could be quite scary for vendors

- Timely repair must be offered for newly found vulnerabilities. Again, no time is set for the lifespan of the product

There are some exceptions for devices that can’t reasonably be made, though mitigation actions must be specified. There is also potential for the vendor to demonstrate instead that they comply with a recognised security standard.

So you make IoT devices?

It’s time to act NOW and get your house in order in terms of security. Otherwise you run the risk of blocking yourself out of a critical market.

Consumers will be looking for differentiators; security will become more important, particularly as your competitors advertise their product as ‘compliant with US government IoT security standards’ or similar

Don’t give them that opportunity; up your game and make your product secure

Here are some simple steps to take:

https://www.pentestpartners.com/security-blog/iot-security-testing-methodologies/

https://www.pentestpartners.com/security-blog/advice-for-iot-device-manufacturers/

What about security researchers?

This has been misinterpreted by many as a carte blanche for security researchers to carry out good faith research to help improve the state of IoT security without fear of prosecution.

The draft bill doesn’t actually say that. What it does say is :

“in good faith, engaged in researching the cybersecurity of an Internet-connected device of the class, model, or type provided by a contractor to a department or agency of the United States”

I’m paraphrasing, but essentially the device being researched or similar has to be used in by a US government agency or department.

However, more important is the definition of ‘good faith research’. When does exercising of an IoT API become good faith research? Does a script kiddie have a defence for deliberately trying to extract customer data from that API? Do they play that card only if they’re detected? How does one determine intent and therefore whether the research was in good faith?

However, more important is the definition of ‘good faith research’. When does exercising of an IoT API become good faith research? Does a script kiddie have a defence for deliberately trying to extract customer data from that API? Do they play that card only if they’re detected? How does one determine intent and therefore whether the research was in good faith?

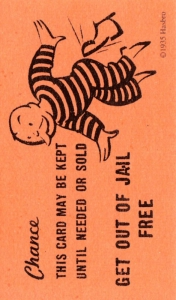

This is an important point – we could inadvertently weaken the DMCA, CFAA and related legislation in other jurisdictions by implementing a ‘get out of jail free because I was doing research’ card Or legitimate well-intentioned researchers could be ensnared if this legislation is implemented poorly.

A subject for extensive debate by lawmakers

Where does it fall short?

These aren’t direct criticisms as we’re really supportive of the draft bill, however there are some areas that could do with attention. Doubtless these will come out during debate:

- NIST isn’t a great vulnerability database for generic application and hardware security flaws. It would be better to add references to OWASP or similar resources of vulnerability classes rather than specific point issues with one product

- For example, SQL injection in a custom written app simply wouldn’t feature in NIST, but would be covered by OWASP

- Similarly, I’m not aware of a database of hardware security flaws, so what would one reference instead? That’s a deeper issue!

- Some RF protocols are designed to use no credentials at all. Examples are ANT+ for fitness trackers and Bluetooth Low Energy.

- Are we saying that these protocols will be simply deprecated, or will more secure versions (e.g. BLE bonding through long term key exchange) be mandated?

This could lead to a huge product churn as vast numbers of consumer’s existing devices become obsolete almost overnight

We think there’s also a gap in relation to consumer personal data stored on the device hardware. For example, if we can extract memory or other resources from the device, we could potentially recover wi-fi keys and other personal data.

I’m not convinced that’s explicitly covered by the draft bill.

Lots to be discussed!

Litigation in the meantime

Lawyers are great at finding ways to exploit existing laws for class actions, particularly around privacy

The recent WeVibe lawsuit was a good example of getting IoT security wrong. The settlement was for around $3.7M – a costly mistake

Several others are in progress currently, though others have been dismissed. An action against Bose is quite interesting, claiming similar data gathering and user tracking for users of its ‘smart’ headphones

Product bans have been effective too: My Friend Cayla has been classed as an illegal covert spying device in Germany and been banned. That’s one way of screwing up a potential market for your IoT device!

Federal Trade Commission complaints have also been used to drive secure behaviour:

ASUSTek Computer Inc (better known to us all as Asus) settled an FTC complaint that potentially binds them to support product for a minimum of 20 years:

The complaint: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2016/02/asus-settles-ftc-charges-insecure-home-routers-cloud-services-put

ASUS responds: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/160222asusagree.pdf – see page 6

Other useful resources and legislation

Various efforts are being made in the EU, particularly around lifespan of IoT devices: Revolv hub users lost access to their devices after it was acquired by Google’s Nest, which resulted in another FTC settlement

Various efforts are being made in the EU, particularly around lifespan of IoT devices: Revolv hub users lost access to their devices after it was acquired by Google’s Nest, which resulted in another FTC settlement

https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/business-blog/2016/07/what-happens-when-sun-sets-smart-product

ENISA are working on IoT security, this time with some support from some chip vendors. A good paper, but the motivation of the chip vendors is clear: they’re keen to sell their more expensive, more secure IoT chipsets!

There is also a question around Right to Repair, which will potentially make securing IoT device firmware harder.

Conclusion

Poor IoT security will shortly not become an option if manufacturers want to sell their product in to key markets.

Litigation has already happened in IoT. Legislation has already been used to kill off IoT product and plenty more of it is coming. Regulation and standards are being developed right now.

It would be a brave manufacturer who continued to develop and ship IoT product without paying serious attention to their security

You can guarantee that IoT manufacturers will be rushing to update their terms of use too; doubtless specifying limited product support lifespans